Monday 29 December 2008

A look at the arguments used by the Danish resistance to justify their assassinations of informers during the Nazi occupation.

In response to a question from Peter Tatchell about the legitimacy of assasinating mass-murdering dictators, Mugabe in particular, Norm has a few words to say, and Johnny Guitar up North has many more. Both of them reproduce this quote from Tatchell’s piece:

Assassinating Adolf Hitler in 1933 probably would have been morally justified to prevent a greater evil – the Holocaust and second world war. But even then, I would see the act of killing Hitler as wrong – albeit the lesser of two evils.

Norm sees Hitler in 1933 as a poor comparison to Mugabe in 2008, where in the case of Mugabe such devastating results of his actions are already known, though not the full results as the disaster is ongoing. On Mugabe he makes the elementary case that the right to self-defence applies.

Johnny Guitar views the question as totally pointless, doubting whether killing Hitler would have prevented the horrors to come, but sees Tatchell’s answer as useful “to illustrate just how completely absurd and immoral the pacifist argument actually is.”

I agree with JG that daydreams of assassinating Mugabe are a distraction from serious debate on how to remove his regime from power, but the question of whether political assassination can ever be justified is important outside of that context. To leave the question hanging in the air seems dangerous when so many people are prepared to portray certain democratic leaders as being on the same level as dictators or terrorists.

My starting point on this is that maintaining and expanding democracy and the rule of law is the most effective way of preventing the rise to power of mass-murderers. From there I think an answer on shooting Hitler can be narrowed down as follows: Assassinating Hitler in the first two months of 1933 would have been murder. A democracy was still in existence. There was still recourse to law. To resort to murder would have been a destabilising attack on democracy and the rule of law.

But in the second half of 1933 it would have been possible to make a reasonable argument that assassinating Hitler was justifiable. There was no longer a democracy in Germany, Hitler presented a clear threat to life and liberty for a large number of the population, and they had no recourse to any system of law independent of the dictatorship.

As to where and when and how such an argument could have been made, that’s another set of questions, leading back to a piece of history I stumbled across when writing my post on Danish cartoonists during the Nazi occupation.

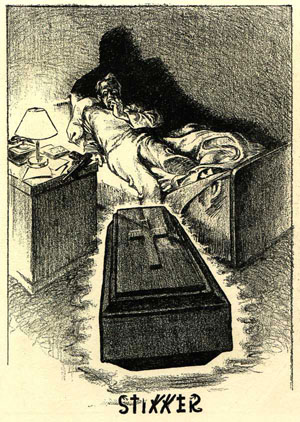

Stikkerens skæbne (The Informer’s Fate), drawing for an underground newspaper by Gustav Østerberg, 1944, reproduced in Besættelse: Tegninger 1940-45, Samlerens Forlag, 1945. More in Danish here.

In the latter period of the occupation, informers were a serious threat to the Danish Resistance. In the Autumn of 1943 the Danish Liberation Council (Frihedsrådet), made up of representatives from the major resistance groups, agreed unanimously that it was necessary to “liquidate” informers, that the Resistance couldn’t continue unless action was taken.

The Liberation Council first considered the possibility of setting up a secret court to try a case before carrying out a liquidation. But this idea was dropped, partly because there wasn’t time for such a procedure if there was a danger that an informer might go to the Gestapo with dangerous information, and partly because liquidations were not to be seen as punishments, but as defensive actions by the Resistance.

In Copenhagen, two large Resistance groups, Holger Danske and BOPA were responsible for most killings of those believed to be informers. In Jutland most liquidations were carried out by specialist groups that could be called in by local Resistance members when they believed they had discovered an informer.

At first liquidations took place as a rule only after careful investigation, and after permission was granted from someone higher in the Resistance movement. But as the fight with the occupation forces intensified and the numbers of liquidations increased, it became more common for groups to decide on their own initiative to carry out a killing. About 400 were killed in all. Some mistakes were made. Nevertheless practically all those killed had in one way or another sided with the Nazis.

The German occupation forces responded with revenge killings, beginning with the murder of the outspoken playwright and priest Kaj Munk on January 4th 1944. Over 100 Danes were victims of these revenge killings. The revenge killings were part of a wider Nazi policy of using terror in response to the Resistance, rather than police work. This policy was adopted on the direct orders of Hitler, and was predominantly carried out by Danish collaborators.

In August 1944, the Folk og Frihed (People and Freedom) underground journal published an article arguing that:

“In the Danish society founded on law which must be rebuilt, everyone who has killed another person stands responsible for their actions, and it will therefore be necessary to hold a police investigation or legal inquiry every case.”

And further that:

Without a doubt good Danes who have taken it upon themselves to eradicate informers will on their own initiative report themselves [after the war] and account for their actions. The necessity of this will be obvious, because neither the case nor those concerned can bear that such a thing be kept secret, and because there must be confidence that possible or alleged abuse will be uncovered and punished.

Turning to what the result of a legal inquiry would be for killers of informers, the Folk og Frihed article asserted that “it is a given that a healthy and intrinsic sense of justice will demand that they be acquitted,” but questioned how would these cases would actually stand in law. Danish law regarding self-defence was outlined, or rather what in Danish is called nødværge, or emergency-defence.

Emergency-defence is dealt with by Paragraph 13 of the Penal Code, which ‘Actions taken in emergency-defence are penalty-free, in so far as they have been necessary to oppose or avert an underway or impending unjust attack, and do not exceed, what with regard to the dangerousness of the attack, the attacker’s person, and the rights of the party under attack, is justifiable.’

So for emergency-defence to apply, the action must have been both necessary and justifiable. This applied to the killing of an informer, it was argued.

This is necessary, that is to say there is no gentler means than the killing of informers by which to prevent their informing, which would regularly would result in to person informed on being killed; the law does not demand that the threatened attack should be directed against the one carrying out the act of emergency defence. [...] Furthermore, as it is the life of the informed upon that is at risk, then the killing of the informer does not exceed what is justifiable. Finally it can be emphasised that informing naturally is an ‘unjust attack.’

The concept of an emergency-defence attack rests on the consideration that the exclusive right of the State to punish must bear the qualification that the private person has a right to attend to the defence of their own or others’ rights, where the State’s assigned law enforcers cannot take charge. This fundamental point of view, which recurs in the law of all civilised states, is also applicable to a high degree in the existing situation.

It is also normally emphasised as something characteristic of an emergency-defence situation that it must be of such a character that in itself normally leaves no doubt as to the attack’s illegality. The Penal Code has in mind on the whole a reaction to an acute attack situation. This is what has raised some doubt as to how widely the emergency-defence point of view kan be applied to the killings of informers, which seldom are carried out in direct connection with the act of informing. However this cannot be conclusive. The words of the Penal Law are fulfilled, in that they only require an ‘impending unjust attack’ and that the attack is ‘impending.’

The concept of an emergency-defence attack rests on the consideration that the exclusive right of the State to punish must bear the qualification that the private person has a right to attend to the defence of their own or others’ rights, where the State’s assigned law enforcers cannot take charge. This fundamental point of view, which recurs in the law of all civilised states, is also applicable to a high degree in the existing situation.

It is also normally emphasised as something characteristic of an emergency-defence situation that it must be of such a character that in itself normally leaves no doubt as to the attack’s illegality. The Penal Code has in mind on the whole a reaction to an acute attack situation. This is what has raised some doubt as to how widely the emergency-defence point of view kan be applied to the killings of informers, which seldom are carried out in direct connection with the act of informing. However this cannot be conclusive. The words of the Penal Law are fulfilled, in that they only require an ‘impending unjust attack’ and that the attack is ‘impending.’

The article follows the main argument on emergency-defence with a brief consideration of how the existence of a state of war might supplement such an argument, and closes with mention of the constitutional power of the crown to grant amnesty should the argument fail.

In October of 1944 Folk og Frihed published one of the best known underground books of the occupation, Der brænder en Ild (A Fire Burns). The book was re-issued after the war in a legal version with all of the contributors names added.

Amongst them was author Martin A. Hansen, whose contribution, Dialog om Drab og Ansvar (Dialogue on Killing and Responsibility), imagined Socrates in dialogue with his friend Simias defending the killing of informers.

In 1953 he commented on his defence as follows:

If anyone were to read Dialogue on Killing and Responsibility, they would perhaps not feel so much the troubles of distant nights. On the other hand they would surely notice, that the Dialogue foresees something of the fate of those who were the instrument, the killers. Bad times might come for them. And they did come. The reader would further notice that the Dialogue is seriously mistaken on another point. It declares that these judgements and liquidations would, after the war, be voluntarily set before Danish courts, so as to lay the burden of these emergency-defence measures upon the shoulders of the people by means of a legal act. In this I was completely mistaken.

An indication that this is how it would happen was in those times a condition one had to make, the only condition I saw myself justified in setting out, before tackling this problem of external origin. For other reasons one couldn’t evade it, once one was on board and approved action. I did however receive the requested indication: decisions would be re-examined later. I don’t know from whom the message came, and I haven’t attempted to trace it. There were also many who believed that was how it should be. It didn’t happen. That was a mistake.

An indication that this is how it would happen was in those times a condition one had to make, the only condition I saw myself justified in setting out, before tackling this problem of external origin. For other reasons one couldn’t evade it, once one was on board and approved action. I did however receive the requested indication: decisions would be re-examined later. I don’t know from whom the message came, and I haven’t attempted to trace it. There were also many who believed that was how it should be. It didn’t happen. That was a mistake.

Photo from Martin A. Hansen - Fra Krigens Aar til Døden by Ole Wivel, Gyldendal 1969, (source).

After the liberation, Hansen learned that at least two of the fallen amongst the Resistance had joined the fight having been convinced of its legitimacy by his writing. As for those killed as informers, he is described in an essay by Kasper Anthoni as having retained a personal self-imposed guilt for some of killings carried out by the Resistance. In notes from his diaries, published in the literary magazine Heretica in 1953 under the title July 44, he expresses the horror that arose in him when he acknowledged that the words in the Dialogue had been used as a direct justification for killing:

In forming a nakedly honest justification for the liquidation of informers, the justifier must make himself perfectly clear, who he is and what he is doing. He hands a tool on to others who are going to use it. Ideally they are, surely, just as obliged to themselves take a position and look the dangers in the eye. But several will of course do it via him, that is why he has been given the job. They keep to his reasoning. And which one it is that can’t avoid responsibility is easy to see.

From the underground newspaper De frie Danske (The Free Danes), April 1944, photographs of informers.

In August 1945 the Social Democrat member of parliament Professor Hartvig Frisch said in a radio broadcast that the killings of informers by the Resistance was murder. Though he had a long record of anti-fascist beliefs, his 1933 book Plague on Europe being banned under the Nazi occupation, he had in 1943 also condemned acts of sabotage by the Resistance as terrorism. His argument on the killings of informers was that they were strategically unwise “as the Germans had all of the resources of power, and one could foresee that the result would be a whole explosion of murders of quite random and innocent people.” Further he argued that the effect had been to “brutalize a large part of Danish Youth. One can’t go up to a man and give him six shots in the face, when he opens the door, without it leaving a mark mentally.” He maintained the killings were unnecessary, pointing to Norway where they were avoided.

The resistance group Holger Danske replied with a press release, pointing to parliamentarian Hartvig Frisch’s “distinctly passive position, both personally and in his pronouncements throughout all of the period of fighting.” They made three points:

1. All of the Resistance Movement have in the period of fighting been in agreement that informer-liquidations can only be seen from the point of view of emergency-defence.

2. To all from the highest leadership to the common saboteur, the informer was an extremely serious personal threat, and it was often simply and literally a question of life or death, as to whether the informer was rendered harmless.

3. Holger Danske wish to point out that even though we were soldiers in the Resistance Movement, who by free will showed discipline and did our duty, there has on our side never been any doubt that the informer-liquidations were practically and morally well-founded, and we will stand in full solidarity with the members of the Liberation Council, whose policy on liquidations the Social Democratic parliamentarian now attacks so strongly.

2. To all from the highest leadership to the common saboteur, the informer was an extremely serious personal threat, and it was often simply and literally a question of life or death, as to whether the informer was rendered harmless.

3. Holger Danske wish to point out that even though we were soldiers in the Resistance Movement, who by free will showed discipline and did our duty, there has on our side never been any doubt that the informer-liquidations were practically and morally well-founded, and we will stand in full solidarity with the members of the Liberation Council, whose policy on liquidations the Social Democratic parliamentarian now attacks so strongly.

Hartvig Frisch lost his seat in parliament as a result of his comments, but was re-elected later and served as education minister.

There are a number of comparisons I’d like to make between the killing of informers by the Danish Resistance and other situations, at other times, in other places, but I’ll save them as this is already a rather long post.

Declaration of ignorance: My knowledge on the topic is not any deeper than what you see here, and my sources for the above are all online, albeit mostly in Danish. The translations at least are my own.

My main source for general information on informer-liquidations was an article by historian Bjørn Pedersen written for an educational website run by the 5th of May Committee (connected with the Danish Resistance Veterans organisation), in co-operation with the Danish Ministry of Education, with some further detail from The Museum of Danish Resistance, part of the National Museum of Denmark.

My source on Folk og Frihed and Martin A. Hansen was first of all the Danish Royal Library’s online exhibit of underground publications from the time of Nazi occupation, and secondly the essay by Kasper Anthoni, I sort/hvid og farver: Alvor og humor i efterkrigstidens kortprosa, as well as excerpts from an article by David Bugge, Digterens janushoved, published in Transfiguration vol. 3:2.