Tuesday 1 November 2011

In 1943 two spectacular colour features were released, one in Nazi Germany and the other in Britain. The writers of these opposing propaganda films were friends who had worked together before the war, and who would continue their friendship and artistic collaboration after the war’s end.

‘Münchhausen’ was written by Erich Kästner and directed by Josef von Baky. ‘The Life And Death of Colonel Blimp’ was written by Emeric Pressburger and directed by Michael Powell.

These were two very different films. ‘Münchhausen’ set out to distract its German audience from the difficulties of war with frothy fantasy, while ‘Blimp’ attempted to tackle core issues of how Britain was fighting the war.

The German film ‘Münchhausen’ was written under a pseudonym by Erich Kästner, a writer banned from publishing in Nazi Germany. The British film ‘Blimp’ was advertised with the blurb ‘See The Banned Film’, but was never actually banned in Britain, despite very strong resistance to the production from James Grigg, Secretary of State for War, and from Churchill himself.

MÜNCHHAUSEN

Produced for the Ufa Film Studio’s 25th anniversary, ‘Münchhausen’ was the result of Goebbels’ desire to produce a spectacle to match the best Hollywood had to offer. However in seeking a subject the director appointed with the task, Josef von Baky, turned to Kästner, and it was Kästner who suggested offering Germany’s greatest liar, Goebbels, a film of literature’s greatest liar, Baron Münchhausen.

Like ‘Blimp’ the tale is told through an extended flashback as the Baron tells of his very long life, of his affair with Catherine the Great of Russia, his magical dealings with the sinister Count Cagliostro, his flight on a cannonball, his rescue of a Venetian princess from a Turkish harem, and his voyage to the moon.

Some film writers suggest that ‘Münchhausen’ has little or no propaganda content, but the lavishness of its display at the height of war was its main propaganda purpose. However it may also be possible to find counter-propaganda in Kästner’s script.

For example, there is a speech where the Baron is described as a Copernican man, one who is constantly aware of his humble place in the universe, and who because of this is human.

And there is the episode where Count Cagliostro tempts Münchhausen with a scheme to seize power, first in Courland (Latvia), then Poland. The Baron turns him down with the reply: ‘We two will never see eye to eye on the main thing. You want to rule; I want to live.’

But perhaps most striking is the section set in Venice, a depiction of repressive state power. Casanova warns the Baron and his lover Princess Isabella to ‘Take care, the inquisitors have ten thousand eyes and limbs. Venice has the power to do right and wrong as she pleases.’

Also in this section, there is a scene which perhaps displays Kästner’s discomfort in his position, as the Doge of Venice says to the Balloonist Monsieur Blanchard, ‘I welcome your intended flight. We serve science, and amuse the people. It’s part of a statesman’s art to do one thing and achieve two.’ Blanchard says ‘I serve only science,’ and the Doge replies ‘Retain that superstition. It’s a card in our hand.’

If ‘Münchhausen’ may be seen as a Nazi film with a hidden message of liberalism and humility, then what about ‘Blimp,’ a British film with a liberal anti-establishment reputation gained largely as a result of the enemies it made in the war cabinet?

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF COLONEL BLIMP

‘The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp’ is the story of a British officer, Clive ‘Sugar’ Candy. We first meet him in old age in 1942 as the Home Guard force under his command is defeated in an exercise by a young army officer, Lieutenant ‘Spud’ Wilson. Breaking the rules of the exercise, Spud and his young soldiers capture Candy and his fellow Home Guard officers in a state of undress in the Turkish Baths of the Royal Bathers’ Club. When Spud shows his contempt for Candy and his fellow elderly overweight officers, Candy responds ‘You laugh at my big belly, but you don’t know how I got it! You laugh at my moustache, but you don’t know why I grew it! How do you know what sort of man I was when I was as young as you are, forty years ago.’

And the extended flashback of his life begins, taking us from the Boer War through adventures in Berlin in 1902, thwarted romance, a duel and a friendship with a German Officer, Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff, World War One and marriage, interwar years of Empire, ending with World War Two and the challenge of how to fight Nazism.

‘Blimp’ is seen by some as a stout defence of holding to moral values even in wartime, by others as an argument against following rules when fighting ‘total war’.

The confusion, along with the film’s troubles with government, began with the name ‘Blimp’. The seed of the story lay in an unused scene from an earlier film, a dialogue between youth and age. At some point Powell and Pressburger made a connection between their character Clive Candy and David Low’s character ‘Colonel Blimp’.

David Low, a left-wing cartoonist working in the Evening Standard, had conceived his Colonel Blimp as a satire of right-wing little Englander appeasers throughout the British establishment, a very different character to Powell and Pressburger’s warm romantic image of Clive Candy.

Though his target was much broader, David Low’s Colonel Blimp character was often seen as being particularly aimed at the army, and the term Blimp became synonymous with outdated attitudes in the British military. So it was that when Sir James Grigg at the War Office received a request for the army’s coöperation with the ‘Blimp’ film, alarm bells rang. He denied the film any help from the army, and brought his concerns to Minister of Information Brendan Bracken, and to Churchill.

Churchill’s opinions were very much in line with Grigg’s, that ‘the film would give the Blimp conception of the Army a new lease of life at a time when it is already dying from inanition,’ and that it was ‘of the utmost importance to get stopped.’ (1) but from the MOI came concerns that today look more serious, concerns that the film could be seen as arguing that the rule of law could be set aside in wartime.

From the MOI’s report on the script submitted prior to production:

‘...The script exaggerates the fair play idea to the point of ridicule and does not show those ways in which it has a constructive value. For instance, in the 1917 sequence, Candy fails to get information from the German prisoners: the tougher personality is more successful. It would have been equally ‘true’ if an instance had been selected in which humanity in dealing with individuals had in fact been more efficient than threats.’

‘...This is one of the scenes which suggests confusion of mind on the part of the authors, unless they merely wished to say that we must become like Germans before we can win the war. If this is what they wished to say - and I don’t think it is - then it is a film we can only deplore. It is more likely that their own minds are in conflict and they have rather wantonly played with ideas - some of which are a trifle ‘daring’ - in order to stimulate people to think or (a less generous interpretation) inject sensational elements for Box Office purposes.’(2)

The mock execution, cut from the film.

Prisoner: ‘This is against all international law.’

So what was it that Powell and Pressburger were trying to say? In a response to the MOI’s script report, Powell and Pressburger wrote:

‘We think these are splendid virtues: so splendid that, in order to preserve them, it is worth while shelving them until we have won the war.’(3)

PRESSBURGER AND KÄSTNER: life, work, and friendship.

Born Imre József Pressburger in 1902, Pressburger became an exile before he even left home, as Hungary was divided following the 1914-18 war and he found himself in an enlarged Romania. He went on to study in Prague and Stuttgart, eventually moving to Berlin where he began working as a writer, publishing his first short story in 1928.

He became the more Germanic ‘Emmerich’ Pressburger on his first screen credit for the Ufa film studio, co-writing ‘Abschied’ (Robert Siodmak 1930). While working his second screenplay for Ufa, ‘Das Ekel’ (Franz Wenzler 1931, film now lost) he was joined by a new co-writer and friend Erich Kästner.

Erich Kästner was born in Dresden in 1899. He initially studied to become a teacher at the Lehrerseminar, but was repelled by the experience:

‘Emil and the Detectives’

Ufa bought the rights to produce ‘Emil and the Detectives’, and as Kästner and Pressburger had worked together on ‘Das Ekel’ they were sent off together to work on ‘Emil’. Kästner remembered:

Much of ‘Emil’ was shot on location in Berlin’s streets.

Pressburger and Kästner’s next collaboration was for a young theatre director Ufa had hired, Max Ophüls. For his first film he had chosen a short poem by Kästner as his subject: ‘I’d Rather Have Cod Liver Oil’ (Max Ophüls 1931). Unfortunately no print survives of this comic fantasy of children swapping places with their parents.

The Ufa studio had been owned since 1927 by Alfred Hugenberg, president of the ultra-right Deutsch-Nationale Volkspartei. In 1932 Hugenberg’s party was seeking an alliance with Hitler’s National Socialists, and he began instituting anti-Semetic policies in his companies. Emmerich Pressburger was informed that Ufa would not renew his contract. Hoping the situation would improve, Pressburger continued working as a freelance in Berlin for various studios, including Ufa via independent producers.

Kästner was in Zürich in 1933 when Hitler came to power:

On the 10th of May 1933, largely because of his 1931 novel Fabian, Erich Kästner’s books were burned by the Nazis:

After he fled Berlin in 1933, Pressburger spent two years in Paris before travelling to London. In 1938 he renamed himself Emeric, and that same year a fellow countryman, composer Miklós Rózsa, introduced him to producer Alexander Korda, also Hungarian. Pressburger’s first script for Korda was ‘The Spy in Black,’ (1939) directed by Michael Powell. It was the start of a long and fruitful partnership between writer and director.

At the war’s end Emeric Pressburger tried to regain contact with his mother in Hungary, only to learn that the 20,000 strong Jewish population of her home town Miskolc had been deported to Auschwitz by the retreating Nazis in 1944. She had not survived.

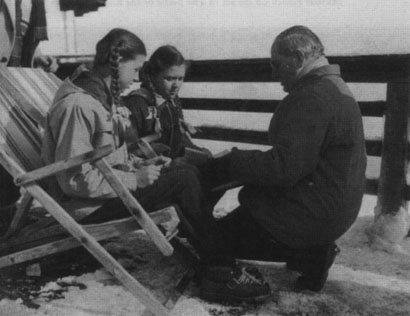

Pressburger directing ‘Twice Upon A Time’ on location in Kitzbühel. Photo from Emeric Pressburger: The Life and Death of a Screenwriter.

In January 1951, taking a family holiday, Pressburger returned to Kitzbühel, the Austrian resort where he and Erich Kästner had stayed twenty years earlier while writing the film adaptation of ‘Emil and the Detectives.’ While there he was invited to a screening of ‘Das Doppelte Lottchen,’ based on the children’s book by Kästner, and directed by Josef von Baky, the director of ‘Münchausen.’

Pressburger greatly enjoyed the film, and the following year directed an English language version titled ‘Twice Upon a Time’ (released 1953) for Korda. It was Pressburger’s first and only attempt at directing, however, and did not go well. There are no longer any prints of the film available for viewing. The story was remade successfully by Disney as ‘The Parent Trap’ (1961). The English translation of the novel is titled ‘Lottie and Lisa.’

FURTHER READING

In 2003 , during a parliamentary debate on the War on Terror, Dr Julian Lewis MP, a Conservative Shadow Defence Minister, invoked Powell and Pressburger’s ‘Blimp’ in support of his argument that the rules of peacetime can be set aside during war, even to the extent of allowing torture of terrorist suspects under certain circumstances. You can read his comments here.

Steve Crook’s Powell and Pressburger Pages website has a big section on ‘Blimp’. It includes this piece on how Low lost control of his monstrous creation. And this 1985 article by Richard Combs reviews the film’s reviewers, and their sometimes wildly contradictory interpretations of the film. However it’s left to Stephen Bourne to tell of Colonel Blimp - a gay icon.

SOURCES

(1) Ian Christie (editor), Powell & Pressburger, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Faber and Faber, 1994, p. 42-43.

(2) ibid. p. 33.

(3) ibid. p. 37.

(4) R.W. Last, Erich Kästner, Modern German Authors New Series, Oswald Wolff 1974, p. 13-14.

(5) Erich Kästner, When I Was A Little Boy, Jonathan Cape 1959, p 59.

(6) Kevin Macdonald, Emeric Pressburger: The Life and Death of a Screenwriter, Faber and Faber 1994, p74.

(7, 8) Harrie Verstappen’s Erich Kästner page on his Looniverse website.